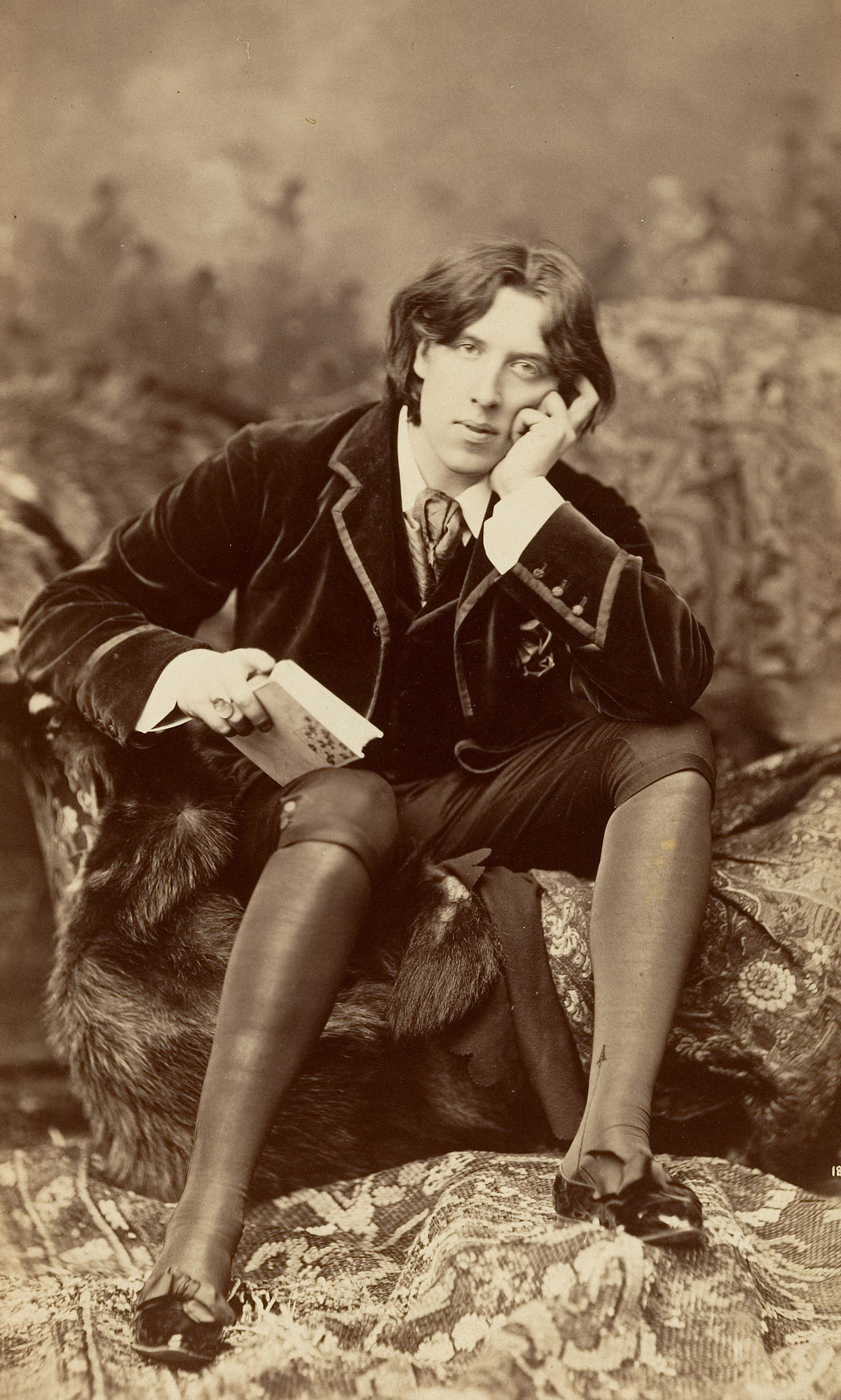

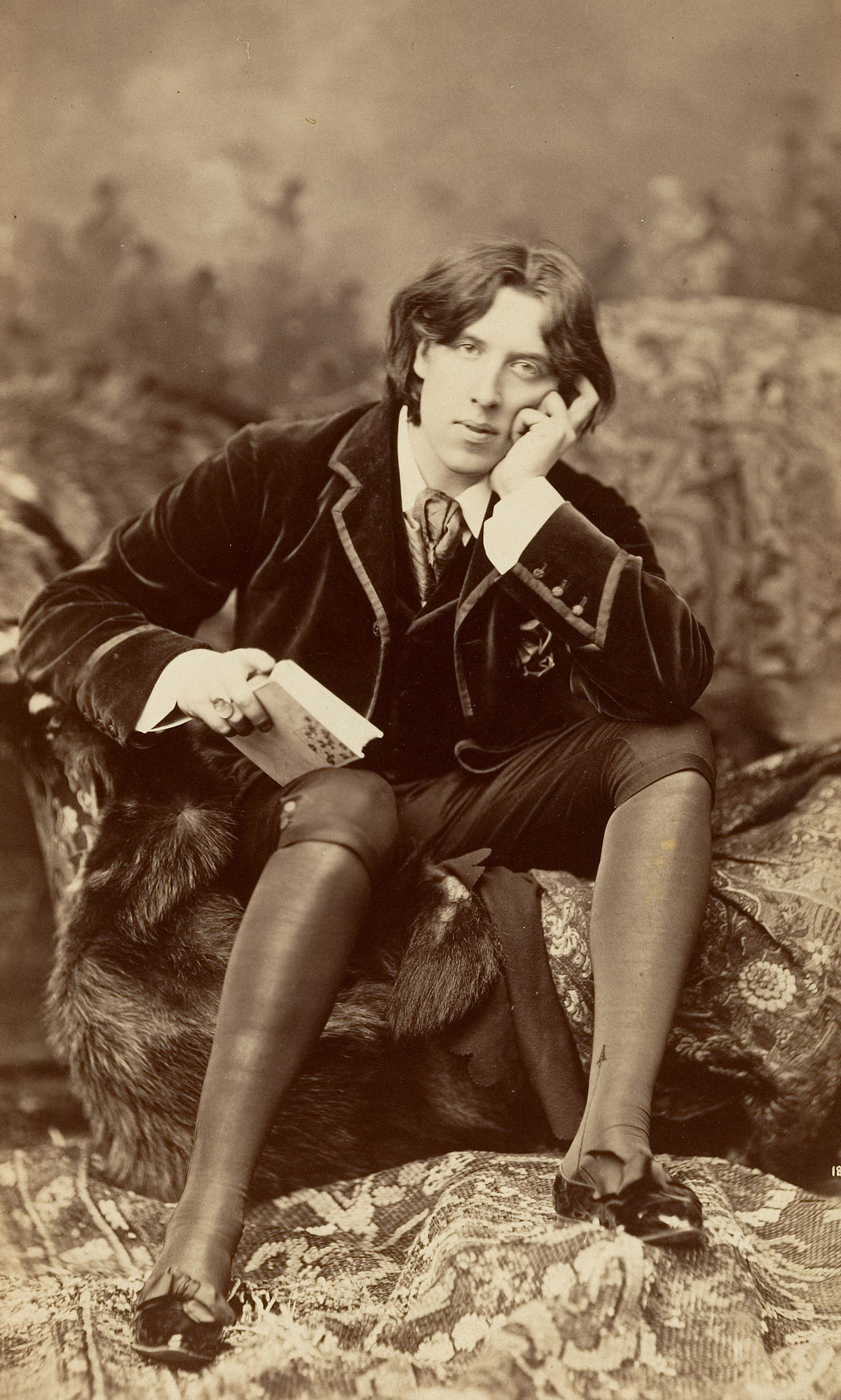

The fairy tale genre has often been associated with childhood and bedtime rituals; with magical images leaping off the page and into the dreams of the sleeping child. "Once Upon a Time" is one of the most famous phrases found in the fairy tale genre and these words uttered aloud conjure up a myriad of images for children and adults alike. Every adult can reflect back on their lives and come up with at least one fairy story in literature or film that was a part of their childhood. Some of these reflections result in fond memories; bringing to life the desire to relive the magic and fantasy found in these beloved tales. Many of these fairy stories began as orated folklore during town or village gatherings, with imagery not well suited to the child. Oscar Wilde, patterned his fairy tales after folklore and that of Hans Christian Anderson; infusing dark imagery and the failings of humankind, as depicted in his publication, The Happy Prince and Other Tales. Contemporary fairy tales specifically written for children, such as The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, and The Chronicles of Narnia by C.S. Lewis, contain many of the elements found in traditional fairy tales; adding magic and mystery as well as moral and religious themes. The conscientious literary scholar; contemplating this genre, may conclude that even the modern versions of the fairy tale and contemporary renderings still may be directed to the adult audience. Well-known tellers of fairy stories, such as Tolkien, Lewis, and Wilde have stated in some form or fashion that the fairy story is truly intended for the adult audience; and their reasons are connected and varying at the same time.

J.R.R. Tolkien is considered the foremost expert on the fairy story and had delivered an often quoted Andrew Lang lecture in 1938 on the fairy tale genre and the elements found in these fantastic stories. His lecture entitled, “On Fairy-Stories”, was later published in an extended format and many literary scholars have written commentary on the points addressed by Tolkien. In Volume 27 of “Mythlore” magazine, published by the Mythopoeic Society in 2008, Jason Fisher reviewed Tolkien’s essay in his article: “Tolkien on Fairy-stories”, citing sections relevant to Tolkien’s beliefs pertaining to the purpose of a fairy-story. In this review, Fisher points out that Tolkien “established positive criteria by which fairy-stories [...] could be evaluated. He built up a working vocabulary for the craft of fantasy that could be used in its criticism” (Fisher 180). Based on this criteria, we can better understand Tolkien’s own thoughts on the genre when he replied in a letter to Michael Straight, the editor of New Republic: “I think that [the] fairy story has its own mode of reflecting ‘truth’, different from allegory, or (sustained) satire, or ‘realism’, and in some ways more powerful. But first of all it must succeed just as a tale, excite, please, and even on occasion move, and within its own imagined world be accorded (literary) belief” (Tolkien 232). In this imagined world, we get to experience real emotion through events and Tolkien prescribes in the A manuscript of “On-Fairy-Stories” the key to generating literary belief: “Joy can tell us much about sorrow, and light about dark but not the other way about. A little joy can often tell more about grief and tragedy than a whole book of unrelieved gloom” (qtd, in Fisher 183). Many fairy tales contain dark or tragic events with small glimmers of light and hope; only at the end. Tolkien called this upturn a eucatastrophe and stated: "I coined the word 'eucatastrophe': the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (...) And I was there led to the view that it produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth… (“Eucatastrophe”)”. Eucatastrophic fairy tales introducing opposition emphasize one of the purposes of fairy tales and its appeal for the adult audience; that of truth. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is full of beautiful contrasts between light and dark and the truth that dwells there; which is explained in wonderful detail in the essay, “The Moral Mythmaker” by Dr. Paul Nolan Hyde.

J.R.R. Tolkien is considered the foremost expert on the fairy story and had delivered an often quoted Andrew Lang lecture in 1938 on the fairy tale genre and the elements found in these fantastic stories. His lecture entitled, “On Fairy-Stories”, was later published in an extended format and many literary scholars have written commentary on the points addressed by Tolkien. In Volume 27 of “Mythlore” magazine, published by the Mythopoeic Society in 2008, Jason Fisher reviewed Tolkien’s essay in his article: “Tolkien on Fairy-stories”, citing sections relevant to Tolkien’s beliefs pertaining to the purpose of a fairy-story. In this review, Fisher points out that Tolkien “established positive criteria by which fairy-stories [...] could be evaluated. He built up a working vocabulary for the craft of fantasy that could be used in its criticism” (Fisher 180). Based on this criteria, we can better understand Tolkien’s own thoughts on the genre when he replied in a letter to Michael Straight, the editor of New Republic: “I think that [the] fairy story has its own mode of reflecting ‘truth’, different from allegory, or (sustained) satire, or ‘realism’, and in some ways more powerful. But first of all it must succeed just as a tale, excite, please, and even on occasion move, and within its own imagined world be accorded (literary) belief” (Tolkien 232). In this imagined world, we get to experience real emotion through events and Tolkien prescribes in the A manuscript of “On-Fairy-Stories” the key to generating literary belief: “Joy can tell us much about sorrow, and light about dark but not the other way about. A little joy can often tell more about grief and tragedy than a whole book of unrelieved gloom” (qtd, in Fisher 183). Many fairy tales contain dark or tragic events with small glimmers of light and hope; only at the end. Tolkien called this upturn a eucatastrophe and stated: "I coined the word 'eucatastrophe': the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears (...) And I was there led to the view that it produces its peculiar effect because it is a sudden glimpse of Truth… (“Eucatastrophe”)”. Eucatastrophic fairy tales introducing opposition emphasize one of the purposes of fairy tales and its appeal for the adult audience; that of truth. Tolkien’s The Hobbit is full of beautiful contrasts between light and dark and the truth that dwells there; which is explained in wonderful detail in the essay, “The Moral Mythmaker” by Dr. Paul Nolan Hyde.

The columnist, Harvey Breit wrote a weekly article in the New York Book Review called the “In and Out of Books”, and in June of 1955, he featured Tolkien. Prior to this publication, he inquired of Tolkien regarding the fantasy genre and the fairy-story; to which Tolkien replied: “I think the so-called ‘fairy story’ one of the highest forms of literature, and quite erroneously associated with children (as such)” (Tolkien 220). In a letter addressed to Dora Marshall, a fan of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien states again: “It remains an unfailing delight to me to find my own belief justified: that the ‘fairy-story’ is really an adult genre, and one for which a starving audience exists” (Tolkien 209). Tolkien’s strong belief that the fairy story was meant for the adult-reader, was no doubt, shared with his friend and fellow Oxford “Inklings”, C.S. Lewis. While they debated over many topics, they both shared the concept that the fairy tale’s themes are meant for the adult.

In her article, “Watchful Dragons and Sinewy Gnomes: C.S. Lewis’s Use of Modern Fairy Tales”, Ruth Berman shares Lewis’s ideas about fairy tales and his hope for this genre stating that “Lewis cited Tolkien as his authority to point out that fairy tales were not necessarily for child-readers, but he was, nevertheless, interested in the fairy tale as a genre that he felt was likely to interest child-readers” (Berman 118). Although C.S. Lewis wrote for children when he wrote The Chronicles of Narnia, he infused them with religious themes; with elements of light and dark (good versus evil); and in a brief essay he shares his feelings that “the fairy tale form might allow him to write about religious themes in a way that would not be obviously religious…” (Berman 118); these themes are not necessarily picked up by a child but rather by an adult reader. Tolkien supported Lewis in the idea of religious themes when he stated: “Myth and fairy-story must, as all art, reflect and contain in solution elements of moral and religious truth (or err), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary ‘real world” (Tolkien 144). The original folk tale (fairy tale) has religious elements, often as a warning to stay on the path, as in “Little Red Riding Hood”. Redemption comes when the knight in shining armor appears; waking the sleeping princess; literally raising her from the dead; similarly, Jesus Christ raises Jarius’s daughter from the dead (Mark 5). These images, familiar to God-fearing individuals, are necessary for understanding the underlying conflicts between light and dark. We see this imagery in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, when the Christ figure is represented by the lion, Aslan, and the Devil is embodied within Queen Jadis, the White Witch. The child only sees the fantastic story with talking animals and a realm of magic. The adult-reader grasps the danger surrounding Edmund and weeps upon Aslan’s sacrifice. C.S. Lewis captures the principles of sin and redemption beautifully. Redemption or salvation, a theme found in many fairy tales is the element that penetrates the reader's senses. Joining Tolkien and Lewis, Oscar Wilde also employs these principles with prominent Christ-figures offering redemption for sin.

In her article, “Watchful Dragons and Sinewy Gnomes: C.S. Lewis’s Use of Modern Fairy Tales”, Ruth Berman shares Lewis’s ideas about fairy tales and his hope for this genre stating that “Lewis cited Tolkien as his authority to point out that fairy tales were not necessarily for child-readers, but he was, nevertheless, interested in the fairy tale as a genre that he felt was likely to interest child-readers” (Berman 118). Although C.S. Lewis wrote for children when he wrote The Chronicles of Narnia, he infused them with religious themes; with elements of light and dark (good versus evil); and in a brief essay he shares his feelings that “the fairy tale form might allow him to write about religious themes in a way that would not be obviously religious…” (Berman 118); these themes are not necessarily picked up by a child but rather by an adult reader. Tolkien supported Lewis in the idea of religious themes when he stated: “Myth and fairy-story must, as all art, reflect and contain in solution elements of moral and religious truth (or err), but not explicit, not in the known form of the primary ‘real world” (Tolkien 144). The original folk tale (fairy tale) has religious elements, often as a warning to stay on the path, as in “Little Red Riding Hood”. Redemption comes when the knight in shining armor appears; waking the sleeping princess; literally raising her from the dead; similarly, Jesus Christ raises Jarius’s daughter from the dead (Mark 5). These images, familiar to God-fearing individuals, are necessary for understanding the underlying conflicts between light and dark. We see this imagery in C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe, when the Christ figure is represented by the lion, Aslan, and the Devil is embodied within Queen Jadis, the White Witch. The child only sees the fantastic story with talking animals and a realm of magic. The adult-reader grasps the danger surrounding Edmund and weeps upon Aslan’s sacrifice. C.S. Lewis captures the principles of sin and redemption beautifully. Redemption or salvation, a theme found in many fairy tales is the element that penetrates the reader's senses. Joining Tolkien and Lewis, Oscar Wilde also employs these principles with prominent Christ-figures offering redemption for sin.

Oscar Wilde, best known for his gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, also wrote and published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Tales and A House of Pomegranates. The 2008 publication of both collections contains a thought-provoking introduction by Gyles Brandreth. He explains that these tales, rich in symbolism and imagery, “reflect [Wilde’s] profound knowledge of the Bible and his classical education” (Brandreth vii). Like, Tolkien and Lewis, Wilde’s work was not meant for the child-reader, even though these tales were written in children’s language; “likely to interest the child-reader” (Berman 118). Responding to a letter from the poet Herbert Kersley, Wilde shared that the collection, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, “[is a study] in prose, put for Romance’s sake into fanciful form: meant partly for children, and partly for those who have kept the childlike faculties of wonder and joy, and who find in simplicity a subtle strangeness” (qtd, in Brandreth xii). “The Selfish Giant”, found in The Happy Prince and Other Tales, appeals to the child with images of children playing in trees and frolicking through the grass and flowers of the giant's garden. However, this story is full of imagery and symbolism so rich in religious themes, that the child could not completely understand the story’s meaning. The concepts of sin, repentance, and redemption are explored in this fairy tale and the story concludes with the death of the giant and redemption extended through the Christ-child. Wilde’s fairy tales, including The Picture of Dorian Gray, demonstrate the possibilities for redemption, however, they all end on an unresolved or tragic note; breaking away from the traditional eucatastrophic fairy tale, as explained by Tolkien. The phrase “happily ever after” never appears. Jack Zipes, who wrote the Afterword for the 2008 publication of Wilde’s fairy tale collection, stated: “Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales have a religious fervor to them that urges us to reconsider what has happened to the nature of humanity at the dawn of modern civilization” (213). This consideration can only be had by the adult-reader; the child inexperienced and can only enjoy the story.

Oscar Wilde, best known for his gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, also wrote and published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Tales and A House of Pomegranates. The 2008 publication of both collections contains a thought-provoking introduction by Gyles Brandreth. He explains that these tales, rich in symbolism and imagery, “reflect [Wilde’s] profound knowledge of the Bible and his classical education” (Brandreth vii). Like, Tolkien and Lewis, Wilde’s work was not meant for the child-reader, even though these tales were written in children’s language; “likely to interest the child-reader” (Berman 118). Responding to a letter from the poet Herbert Kersley, Wilde shared that the collection, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, “[is a study] in prose, put for Romance’s sake into fanciful form: meant partly for children, and partly for those who have kept the childlike faculties of wonder and joy, and who find in simplicity a subtle strangeness” (qtd, in Brandreth xii). “The Selfish Giant”, found in The Happy Prince and Other Tales, appeals to the child with images of children playing in trees and frolicking through the grass and flowers of the giant's garden. However, this story is full of imagery and symbolism so rich in religious themes, that the child could not completely understand the story’s meaning. The concepts of sin, repentance, and redemption are explored in this fairy tale and the story concludes with the death of the giant and redemption extended through the Christ-child. Wilde’s fairy tales, including The Picture of Dorian Gray, demonstrate the possibilities for redemption, however, they all end on an unresolved or tragic note; breaking away from the traditional eucatastrophic fairy tale, as explained by Tolkien. The phrase “happily ever after” never appears. Jack Zipes, who wrote the Afterword for the 2008 publication of Wilde’s fairy tale collection, stated: “Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales have a religious fervor to them that urges us to reconsider what has happened to the nature of humanity at the dawn of modern civilization” (213). This consideration can only be had by the adult-reader; the child inexperienced and can only enjoy the story.

Whether the imagery is overtly religious, as found in Wilde’s works or close to the vest, as in Tolkien’s tales; adults love fairy tales. And quite simply, because adults are children who have grown-up and have kept their “childlike faculties”. Tolkien’s fairy story, The Hobbit, is written in children’s language, by the child who grew up, Bilbo Baggins; for every hobbit is a child. Tolkien once said of himself: “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size)” (Tolkien 288). The fairy tale will still draw the attention of the child-reader; providing excitement and pleasure mixed with magical opportunities to explore. Literary belief built upon truth causes the adult-reader to be moved. The light and dark of truth remain in the realm of adulthood, and the tale reawakens the child within.

Whether the imagery is overtly religious, as found in Wilde’s works or close to the vest, as in Tolkien’s tales; adults love fairy tales. And quite simply, because adults are children who have grown-up and have kept their “childlike faculties”. Tolkien’s fairy story, The Hobbit, is written in children’s language, by the child who grew up, Bilbo Baggins; for every hobbit is a child. Tolkien once said of himself: “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size)” (Tolkien 288). The fairy tale will still draw the attention of the child-reader; providing excitement and pleasure mixed with magical opportunities to explore. Literary belief built upon truth causes the adult-reader to be moved. The light and dark of truth remain in the realm of adulthood, and the tale reawakens the child within.

“Eucatastrophe.” Tolkien Gateway, 20 June 2009, tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Eucatastrophe.

Fisher, Jason. Mythlore, vol. 27, no. 1/2 (103/104), 2008, pp. 179–184. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26814574. Accessed 23 Feb. 2020.

Hyde, Paul N. "The Moral Mythmaker: The Creative Theology of J. R. R. Tolkien." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 3, no. 3 (2002). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol3/iss3/28

Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales. 2nd ed., W.W. Norton Et Company, 2017.

Tolkien, J. R. R., et al. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Wilde, Oscar. Complete Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde. Signet Classics, 2008.

The columnist, Harvey Breit wrote a weekly article in the New York Book Review called the “In and Out of Books”, and in June of 1955, he featured Tolkien. Prior to this publication, he inquired of Tolkien regarding the fantasy genre and the fairy-story; to which Tolkien replied: “I think the so-called ‘fairy story’ one of the highest forms of literature, and quite erroneously associated with children (as such)” (Tolkien 220). In a letter addressed to Dora Marshall, a fan of The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien states again: “It remains an unfailing delight to me to find my own belief justified: that the ‘fairy-story’ is really an adult genre, and one for which a starving audience exists” (Tolkien 209). Tolkien’s strong belief that the fairy story was meant for the adult-reader, was no doubt, shared with his friend and fellow Oxford “Inklings”, C.S. Lewis. While they debated over many topics, they both shared the concept that the fairy tale’s themes are meant for the adult.

Oscar Wilde, best known for his gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, also wrote and published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Tales and A House of Pomegranates. The 2008 publication of both collections contains a thought-provoking introduction by Gyles Brandreth. He explains that these tales, rich in symbolism and imagery, “reflect [Wilde’s] profound knowledge of the Bible and his classical education” (Brandreth vii). Like, Tolkien and Lewis, Wilde’s work was not meant for the child-reader, even though these tales were written in children’s language; “likely to interest the child-reader” (Berman 118). Responding to a letter from the poet Herbert Kersley, Wilde shared that the collection, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, “[is a study] in prose, put for Romance’s sake into fanciful form: meant partly for children, and partly for those who have kept the childlike faculties of wonder and joy, and who find in simplicity a subtle strangeness” (qtd, in Brandreth xii). “The Selfish Giant”, found in The Happy Prince and Other Tales, appeals to the child with images of children playing in trees and frolicking through the grass and flowers of the giant's garden. However, this story is full of imagery and symbolism so rich in religious themes, that the child could not completely understand the story’s meaning. The concepts of sin, repentance, and redemption are explored in this fairy tale and the story concludes with the death of the giant and redemption extended through the Christ-child. Wilde’s fairy tales, including The Picture of Dorian Gray, demonstrate the possibilities for redemption, however, they all end on an unresolved or tragic note; breaking away from the traditional eucatastrophic fairy tale, as explained by Tolkien. The phrase “happily ever after” never appears. Jack Zipes, who wrote the Afterword for the 2008 publication of Wilde’s fairy tale collection, stated: “Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales have a religious fervor to them that urges us to reconsider what has happened to the nature of humanity at the dawn of modern civilization” (213). This consideration can only be had by the adult-reader; the child inexperienced and can only enjoy the story.

Oscar Wilde, best known for his gothic novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, also wrote and published two collections of fairy tales: The Happy Prince and Other Tales and A House of Pomegranates. The 2008 publication of both collections contains a thought-provoking introduction by Gyles Brandreth. He explains that these tales, rich in symbolism and imagery, “reflect [Wilde’s] profound knowledge of the Bible and his classical education” (Brandreth vii). Like, Tolkien and Lewis, Wilde’s work was not meant for the child-reader, even though these tales were written in children’s language; “likely to interest the child-reader” (Berman 118). Responding to a letter from the poet Herbert Kersley, Wilde shared that the collection, The Happy Prince and Other Tales, “[is a study] in prose, put for Romance’s sake into fanciful form: meant partly for children, and partly for those who have kept the childlike faculties of wonder and joy, and who find in simplicity a subtle strangeness” (qtd, in Brandreth xii). “The Selfish Giant”, found in The Happy Prince and Other Tales, appeals to the child with images of children playing in trees and frolicking through the grass and flowers of the giant's garden. However, this story is full of imagery and symbolism so rich in religious themes, that the child could not completely understand the story’s meaning. The concepts of sin, repentance, and redemption are explored in this fairy tale and the story concludes with the death of the giant and redemption extended through the Christ-child. Wilde’s fairy tales, including The Picture of Dorian Gray, demonstrate the possibilities for redemption, however, they all end on an unresolved or tragic note; breaking away from the traditional eucatastrophic fairy tale, as explained by Tolkien. The phrase “happily ever after” never appears. Jack Zipes, who wrote the Afterword for the 2008 publication of Wilde’s fairy tale collection, stated: “Oscar Wilde’s fairy tales have a religious fervor to them that urges us to reconsider what has happened to the nature of humanity at the dawn of modern civilization” (213). This consideration can only be had by the adult-reader; the child inexperienced and can only enjoy the story. Whether the imagery is overtly religious, as found in Wilde’s works or close to the vest, as in Tolkien’s tales; adults love fairy tales. And quite simply, because adults are children who have grown-up and have kept their “childlike faculties”. Tolkien’s fairy story, The Hobbit, is written in children’s language, by the child who grew up, Bilbo Baggins; for every hobbit is a child. Tolkien once said of himself: “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size)” (Tolkien 288). The fairy tale will still draw the attention of the child-reader; providing excitement and pleasure mixed with magical opportunities to explore. Literary belief built upon truth causes the adult-reader to be moved. The light and dark of truth remain in the realm of adulthood, and the tale reawakens the child within.

Whether the imagery is overtly religious, as found in Wilde’s works or close to the vest, as in Tolkien’s tales; adults love fairy tales. And quite simply, because adults are children who have grown-up and have kept their “childlike faculties”. Tolkien’s fairy story, The Hobbit, is written in children’s language, by the child who grew up, Bilbo Baggins; for every hobbit is a child. Tolkien once said of himself: “I am in fact a Hobbit (in all but size)” (Tolkien 288). The fairy tale will still draw the attention of the child-reader; providing excitement and pleasure mixed with magical opportunities to explore. Literary belief built upon truth causes the adult-reader to be moved. The light and dark of truth remain in the realm of adulthood, and the tale reawakens the child within.

Works Cited

Berman, Ruth. “Watchful Dragons and Sinewy Gnomes: C.S. Lewis's Use of Modern Fairy Tales.” Mythlore, vol. 30, no. 3/4 (117/118), 2012, pp. 117–127. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26815504. Accessed 23 Feb. 2020.“Eucatastrophe.” Tolkien Gateway, 20 June 2009, tolkiengateway.net/wiki/Eucatastrophe.

Fisher, Jason. Mythlore, vol. 27, no. 1/2 (103/104), 2008, pp. 179–184. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26814574. Accessed 23 Feb. 2020.

Hyde, Paul N. "The Moral Mythmaker: The Creative Theology of J. R. R. Tolkien." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 3, no. 3 (2002). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol3/iss3/28

Tatar, Maria. The Classic Fairy Tales. 2nd ed., W.W. Norton Et Company, 2017.

Tolkien, J. R. R., et al. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000.

Wilde, Oscar. Complete Fairy Tales of Oscar Wilde. Signet Classics, 2008.

No comments:

Post a Comment